Whenever I see news footage of refugees, I always think, “How bad would things have to get before I packed a bag and fled from my home?”

Whenever I see news footage of refugees, I always think, “How bad would things have to get before I packed a bag and fled from my home?”

The answer, of course, is really, really bad, especially when doing so would likely put me in mortal danger and leave me vulnerable, indefinitely, in countless ways.

So I knew that As Far As My Fingertips Take Me — a one-on-one installation performance that’s part of University Musical Society’s No Safety Net 2.0 theater series — would likely challenge me and make the pain of diaspora more tangible. But what I couldn’t have guessed is how strangely attached I’d become to the visible marks it left upon my skin.

Created by Tania Khoury and performed by Basel Zaraa (a Palestinian refugee born in Syria), the experience begins when you bare your left arm to the elbow, sit next to a white wall, pull on a pair of headphones, trustingly extend your arm through a hole in the wall, and listen to a recording of Zaraa telling his own refugee story, accompanied by an atmospheric rap inspired by his sisters’ journey from Damascus to Sweden.

On the recording, Zaraa introduces himself and says, “This is me, touching your arm,” and there’s something both unnerving and comforting about experiencing touch without being able to see its source. First, you feel the pads of your fingers being inked, one by one, and then you feel different areas of your arm being gently drawn upon: a line from one fingertip to a small boat full of people at the center of your palm; and from your wrist to your elbow, a caravan of walking figures, dragging their possessions toward a distinct border.

Zaraa completes the figures before the music ends, leaving you to look at your newly decorated arm and read a long poem (printed on the same wall) that contains the refrain that gives the song you’re hearing its thematic shape: “We only want what everybody wants.” READ THE REST HERE

For more than a quarter-century, Chelsea’s

For more than a quarter-century, Chelsea’s  In October 2019, as Khadija B. Wallace’s grandkids candied apples that would be delivered as a “thank you for your business” gift to several clients of

In October 2019, as Khadija B. Wallace’s grandkids candied apples that would be delivered as a “thank you for your business” gift to several clients of  Each year, after the holidays wrap up, and the long, deep freeze of winter takes hold, Michiganders tend to go into bear-like hibernation, only emerging from their cozy homes long enough to go to work, go to school, or run necessary errands.

Each year, after the holidays wrap up, and the long, deep freeze of winter takes hold, Michiganders tend to go into bear-like hibernation, only emerging from their cozy homes long enough to go to work, go to school, or run necessary errands. Despite the clichéd, eye-roll-inducing notion of creative work that makes you laugh and makes you cry, David Sedaris’ essays are nearly universally adored because they regularly, miraculously achieve just that.

Despite the clichéd, eye-roll-inducing notion of creative work that makes you laugh and makes you cry, David Sedaris’ essays are nearly universally adored because they regularly, miraculously achieve just that. Usually when I see a show for review, I don’t end up on stage, singing a Pogues song.

Usually when I see a show for review, I don’t end up on stage, singing a Pogues song. “Sometimes joy has a terrible cost” is a quintessential lyric in William Finn’s autobiographical musical, A New Brain.

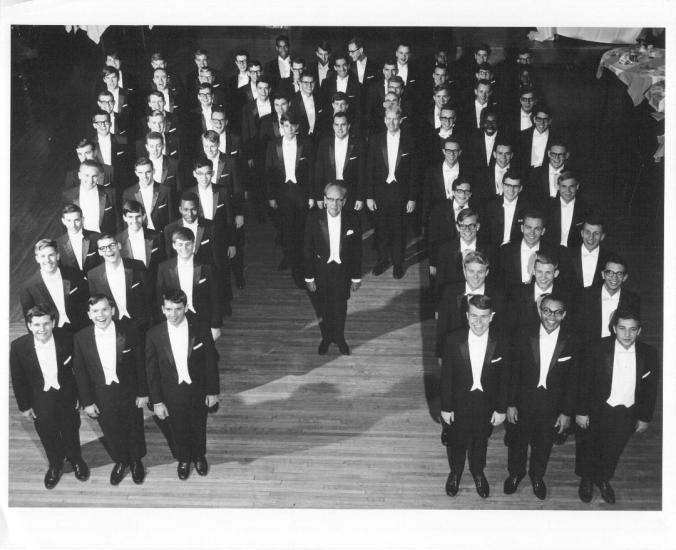

“Sometimes joy has a terrible cost” is a quintessential lyric in William Finn’s autobiographical musical, A New Brain. On May 15, 1967, nearly five dozen members of the U-M Men’s Glee Club boarded a bus at the Michigan Union to embark on an eight-week world tour. Many of them had never traveled west of the Mississippi before, let alone to the other side of the world.

On May 15, 1967, nearly five dozen members of the U-M Men’s Glee Club boarded a bus at the Michigan Union to embark on an eight-week world tour. Many of them had never traveled west of the Mississippi before, let alone to the other side of the world. Last year, while visiting my 76-year-old father in North Carolina during the holidays, he casually mentioned that he’d taken out a reverse mortgage – which is to say, he’d taken out a loan against the value of his fully-paid-for home.

Last year, while visiting my 76-year-old father in North Carolina during the holidays, he casually mentioned that he’d taken out a reverse mortgage – which is to say, he’d taken out a loan against the value of his fully-paid-for home. Nobody can hold your feet to the fire quite like an eight-year-old.

Nobody can hold your feet to the fire quite like an eight-year-old.